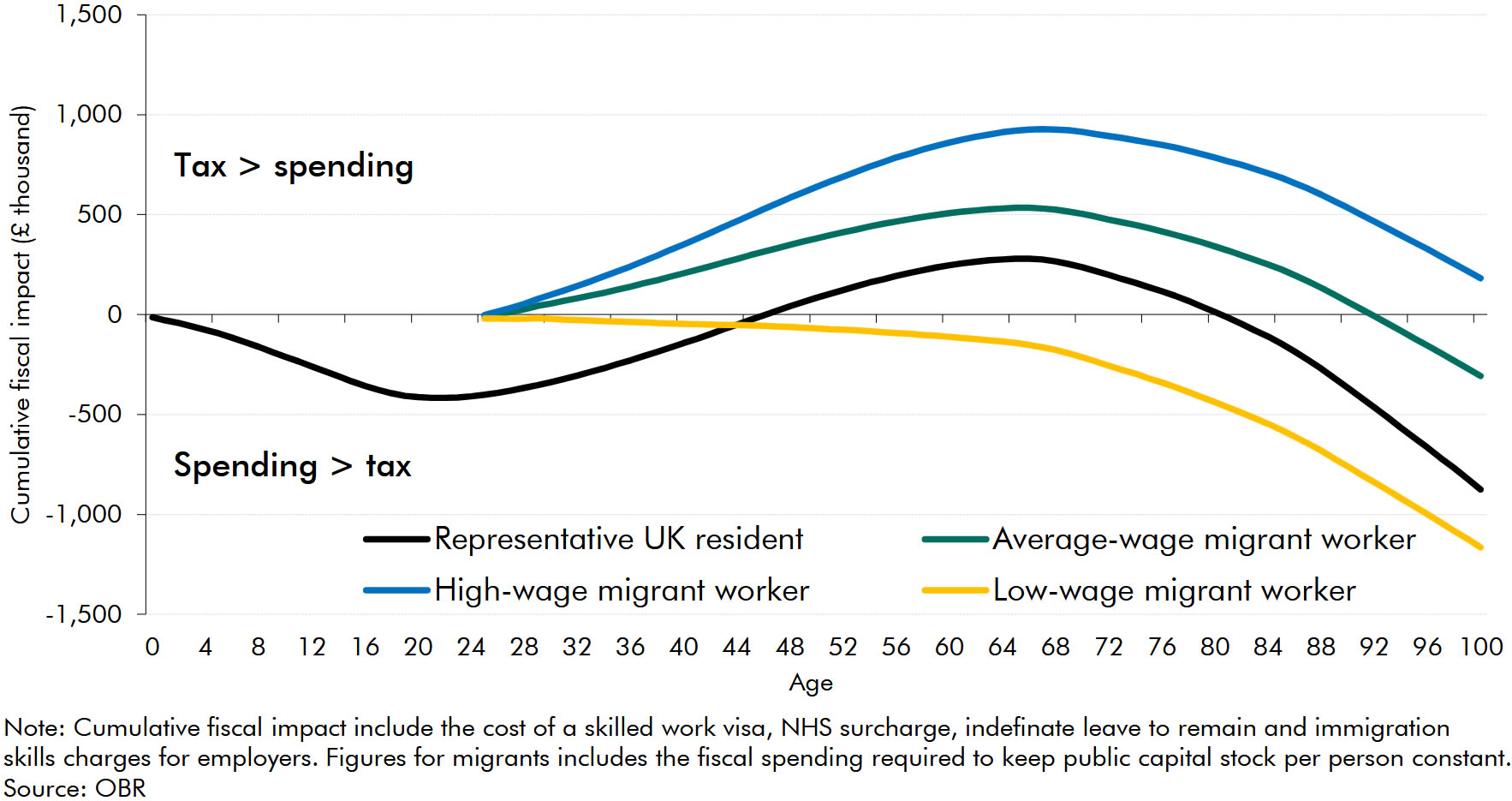

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) predicts that low-wage migrants, on average, are a fiscal burden regardless of length of stay. The best case scenario, from a fiscal point of view, is if a low-wage migrant arrives at age 25 and stays for only one year, which is estimated to cost the taxpayer £20,000. If a low-wage migrant decides to stay indefinitely, as Oxford University estimates that around 30% will do, then the cost balloons to £465,000.

Last month, a 40-year-old woman in Wales, who was denied a life-extending cancer drug, tragically died. The drug, Enhertu, is not available in England or Wales due to high costs. A course of treatment is valued around £118,000.

Who voted for low-wage immigrants over cancer treatment for British citizens?

Reference to image: ‘Low-wage’ means a salary of £18,715 (half the UK average), ‘high-wage’ means a salary of £ 48,659 (30% higher than the UK average). Source: Office of Budget Responsibility, Fiscal Risk and Sustainability report — March 2024, chart 4.13

In 2023, there were a total 337,240 work visas granted to applicants, of which 54% were for low-wage work.

That means, if we consider only the 30% of low-wage migrants that stay indefinitely, low-wage work visas for a single year (2023) is estimated to eventually cost the government over £25.4 billion (337,240 work visas granted x 54% being low-wage work visas x 30% who go on to stay indefinitely x £465,000 individual lifetime fiscal cost).

To put that into perspective, the entire government revenue generated from inheritance tax for the 2023–24 financial year was £7.2 billion, and the significant Conservative austerity measures of 2010–2013 saved a total of £14.3 billion a year.

In other words, the government could, in the long run, avoid future Osbourne/Cameron austerity measures, as well as completely cut all inheritance tax, if they decided to stop all low-wage work visas.

It’s important to highlight a key part of the above statement, “in the long run”. The net cost of low-wage immigration for a single year doesn’t occur in that one year, but over many decades for the duration of the migrant’s lives.

However, even when accounting for these extended timelines, the cumulative fiscal impact raises serious concerns about the sustainability of current low-wage immigration policies and their long-term burden on public finances.

Furthermore, this calculation does not take into consideration the fiscal costs associated with the other 70% of low-wage migrants, as well as family dependents, who are estimated to cost on average even more than low-wage migrants.

One common argument for low-wage immigration is the idea that we need them for roles unattractive to domestic workers. For example, the NHS relies heavily on low-wage workers. However, this creates a problematic cycle. Like a pyramid scheme, we bring in workers to support the NHS, who will eventually burden the NHS, requiring another layer of low-wage immigrants. You don’t need a finance degree to see how this is unsustainable and therefore is not a real, long-term argument. Naturally, there will be some pain if low-wage immigration were to stop, but the options aren’t pain or no pain, it’s pain now, or more severe pain later.

With all this in mind, the government needs to reevaluate its visa policies, particularly focusing on work visas that result in a negative fiscal impact. A logical first step would be cutting the number of visas issued for low-wage positions to zero.